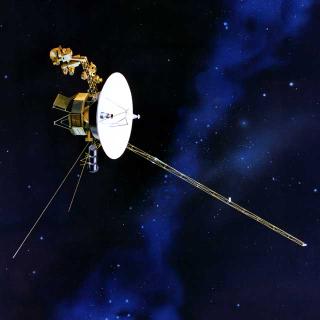

The second thing that captured my imagination this week was the report that Voyager 1 has entered the next stage of its departure from our solar system by crossing the "termination shock" that marks the beginning of the "heliopause."

It's wonderful the way we find these new structures wherever we look, and the edge of the solar system is no exception. You might have thought that waving bye-bye to Neptune and Pluto would mark the probe's entry into empty interstellar space, but it turns out there is a detectable bubble of particles blown out by the sun, and a form of shock wave where the particles slow down from millions of miles per hour to radically slower speeds--maybe even reversing direction back toward the sun like waves lapping on a cosmic beach. This fuzzy line marks the region where the pressure of particles blowing in from other stars becomes more powerful than that of our own sun. Only when it travels beyond this region, which will take another few years, will Voyager enter true interstellar space and become our first probe to the stars.

Voyager wasn't the first vehicle to officially leave the solar system. In 1983 Pioneer 10 first passed the orbit of Neptune while it was temporarily the most distant planet from the sun due to Pluto's eccentric orbit. At the time NASA broadcast its bleeping radio transmissions to mark the event. There was even a toll-free number you could call to hear it live, 24-hours a day. (Had there been an Internet at the time, it would have been online as well, but the Internet had yet to develop.) And yes, I dialed that number and listened.

But Voyager is moving faster, and in 1998 it surpassed Pioneer 10 as the most distant man-made object.

More years have passed, and Voyager is still in the process of leaving. The boundary is that wide. The mission is thirty years old, and the probe may continue to function for another ten or fifteen years. It is now over eight billion miles out--twice the distance to Pluto--and by the time it expires it will be out over ten billion miles. But that will be only two-tenths of one percent of a lightyear, and the nearest star is over four lightyears away, and in a different direction.

Even so, I find this more exciting than anything that has happened in space exploration since the manned moon landings. (More on them another time.) As someone who has grown up through the era of rocketry, I have followed it since I was a small child, when Werner Von Braun and his team of German scientists founded the US missile program, and later the space program. I used to have a scrapbook filled with every photo I could find of rockets and satellites. I even kept a log as each satellite and space probe was launched, giving it up as hopeless when the launches reached into the hundreds (now thousands).

There have been many firsts over the years. Some of them were significant: the first satellite in orbit, the first human in space, first probes to the moon and other planets, first people to visit the moon. Others were merely of passing social interest, or of concern in the "space race" between the USA and the USSR: the first woman, first "space walk," first orbital rendezvous, or the first [insert your nationality here] in space.

There will be other such firsts as we venture forth from our planetary home. And there may be other "space races" in our future--are you watching the Chinese? But there will always be Voyager 1, this first tendril of human construction, a mere bucket of bolts, drifting out among the stars like a bottle in the ocean, bearing a message in case it ever washes up on some far shore, a message that says, "we were here," and which may be read when the human race is no more than an archeological relic.

Tuesday, September 27, 2005

Cosmic Perspectives, Part 2: Voyager

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

A footnote to this:

ReplyDeleteI once read a science fiction novel about a family of colonists who travelled in the first spaceship to another star. Realistically, they had to travel close to the speed of light and also spend time in suspended animation in order to get there within the span of a human life.

Somewhere near the end of the voyage they believed they encountered an alien spacecraft passing them at incredible speed. But when they arrived at their destination they found a thriving human civilization already in place. The ship that had passed them was one of many developed later that could travel faster than the speed of light. It was as if the Pilgrims had set out for the New World in 1620 and sailed into New York harbor in 1920, where they were dwarfed by mammoth steamships and amazed by airplanes in the sky.

The speed of light may never be broken, but even if it isn't we will certainly follow Voyager someday with faster probes aimed at specific stars. Maybe someday the people decoding Voyager's message will be our own far descendents, scattered around the galaxy.